Man’s Evil: Ellis’ Third Irrational Idea

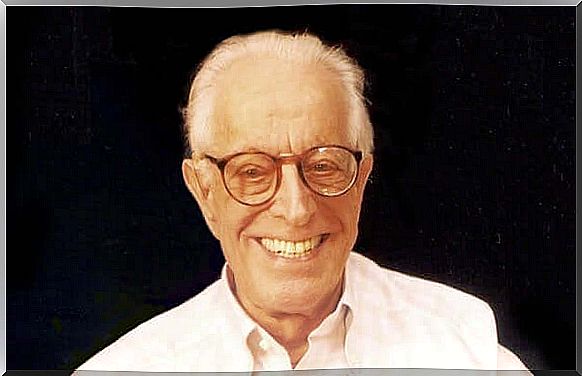

There are certain irrational ideas that are at the base of the functioning of society and, as a consequence, of man; Albert Ellis calls them “freaks”. In fact, many of these irrational ideas underlie the irrational thoughts that cloud our mood, curb our behavior, and cloud our ability to cognize. Ellis’ third irrational idea, which we’ll talk about in this article, also plays this role.

Many of these ideas are inherited from the historical process of each culture and, in our case, many of them come from the tradition and morality of religion, which until recently were present in every corner of our society.

So in this article we’re going to focus on Ellis’ third irrational idea. Although it is considered irrational, many still continue to believe and base their cognitions and actions on it.

Are people bad?

The third irrational idea proposed by Ellis reads as follows:

Many can argue and agree with this idea. There is a tendency to label people as “good” or “bad” depending on the actions they take.

If a person chooses an option that we think is objectionable, we usually label it bad. And not only that: bad people also have to suffer because of their nature or their actions. They need to be punished.

Although, a priori, and again based on the contextual framework and the sociodemographic heritage that we have, this is not an unreasonable idea, Ellis sees it on the basis of irrational thinking, not based on evidence and that abuses absolutes. In other words, it ‘s a toxic way of thinking that doesn’t seem to do us any good.

But why is this idea not true? Are there not bad people who do bad deeds? Don’t they deserve punishment?

The unprovable evil of man

Ellis, in his work Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy (1962), tries to explain why evil is not a fact. He argues, among other things, that the idea that people can be good or bad is part of the ancient theological doctrine of free will.

There were many philosophers (Descartes, Hume and even Kant) who spoke about free will and, above all, about ethics based on free will. If there are good or bad people and there is free will, it means that people are free to do “good” or “evil”.

Somehow, this premise may also indicate that there is an absolute truth, dictated by a “god” or a “natural law”, which determines what goes into “good” and what is part of “evil”.

This doctrine has no scientific basis, and its key words (a god, absolute truth, free will…) cannot be proved or disproved. Therefore, claiming, as a basis, that there are good and bad people does not make sense.

A bad deed doesn’t make a bad person

A bad action, or a wrong action, does not define as “bad” the person who performs it. In fact, although we usually infer that these impulses come from a clearly evil nature, most of the times they occur out of simple ignorance, ignorance or some kind of health condition.

Regardless of these people causing and being responsible for harm to others with their bad actions, this does not mean that they deserve a humiliating and lethal punishment for their ignorance, ignorance or for some type of health condition. On many occasions, when we impose punishment on people who have committed a wrongdoing, it seeks to penalize an alleged wrongdoing.

Does it make sense to punish these aspects? Wouldn’t it make more sense to try to make sure that, next time, that person wasn’t so ignorant, so lacking in knowledge, or didn’t have that health condition? The idea that a man who does something bad is bad has been projected into many sermons from different churches: many religions believe they are guardians of morals.

However, the reality proved to be more complex. One person can give money to another homeless person and come home at night and mistreat your child. A person may not let an elderly person sit on the subway and work 14 hours a day to pay for medical treatment for their father.

A “bad” action does not determine anything, so much so that the definition of “bad” is subjective. Some find something good in bad, and something bad in good.

the fallibility of our nature

Ellis, in his work, argues that it is unrealistic to think that we are going to do everything right. In fact, fallibility is in the nature of the human being; much of your learning comes from trial and error.

Therefore, to say that a person “should” do something, “should” have acted otherwise, is wrong. The use of absolutes and “shoulds” is at the base of all irrational thinking, and the person “should not” have acted that way because man is fallible and can make mistakes.

The usefulness of punishing the bad

Punishment, on many occasions, has unfavorable effects on the learning process. If a person makes a mistake, or a “bad” action, blaming them in a vindictive and angry way can be counterproductive.

When a person makes a mistake out of ignorance, the punishment imposed for his actions will not make him any less ignorant. So, if after the punishment we expect the person to act differently, that doesn’t make much sense. Ellis summarizes this issue with an example:

Furthermore, if a person makes a mistake because of a psychological health condition, blaming him can even “feed” that condition. Guilt, anger, and hostility lie at the root of many psychological disorders.

Faced with this philosophy of blaming, in which children are immersed since very young, blaming for past, present and future mistakes is exalted. Without this blaming, feelings of anxiety, guilt, or depression would have a harder time instilling in us.

Ellis’ third irrational idea in education

Many of us were brought up on the premises that support Ellis’s third irrational idea, making us guilty, afraid of making mistakes, afraid of punishment, and vaguely thinking about what is bad or good. This affects our mood, our way of being and our behaviors.

Therefore, before judging a person’s badness, it is necessary to think several times. Likewise, if a person judges our actions or reprimands them, we must also think about Ellis’s third irrational idea and decide whether our guilt is lawful or not.