Why Do We Insist On Failed Attempts At A Solution?

Problems are one of our biggest concerns. Living is not a simple experience and it is hindered by the natural difficulties that arise from day to day. Even more so when difficulties turn into problems. Today, we will talk specifically about the failed attempts at a solution that we insist on solving these problems.

Problems stagnate and block evolution, in addition to impeding growth, especially when they are not resolved. People end up living with the problem, and its entire ecology revolves around the despotism it exerts.

The transformation of a difficulty into a problem and its perpetuation is the result of failed attempts at a solution. To this, it is necessary to add the aggravating factor that these attempts – in themselves – have also become a problem. That’s because the more you try to solve, the more of the same result you get and the more the original problem is installed in the system.

Solution attempts are a series of actions and interactions aimed at solving the difficulty. These actions are the typical mechanisms a person resorts to when faced with an obstacle.

In general, we human beings do not exploit our creativity in the service of solution attempts. Our conceptual frameworks governed by rational logic (and there are many opportunities where logic is ineffective) encompass a very limited repertoire that does not favor variation in qualitative terms.

However, we move in quantitative terrain: we tend to do more of the same, even though the results do not point in the expected direction and end up leading to failure. The following examples are examples of this.

- Although the child still presents problems in studies, parents continue to resort to private teachers, obtaining slight modifications or none at all.

- The daughter does not want to eat and the mother continues to pressure her with plates of food, generating greater aversion to eating.

- The boss continues to reprimand the ineffectiveness of an employee. This causes more tension and nervousness, which increases its inefficiency.

- Parents order the child not to scream, screaming.

As we see, these ways of acting to solve problems create self-fulfilling prophecies: we talk so much about a topic that we end up building it with our actions.

Why do we repeat failed attempts at a solution?

What are the reasons why we continue to apply the same formula despite its inefficiency? Why do the attempts at solution increase and are repeated even though the opposite result is obtained?

The answers are in our minds, in the way we process information. Thus, the processes and mechanisms we use are based on:

- The search for causes: our thinking is based on the logic of linear why, cause-effect, that is, whenever we see a result, we try to explain to ourselves the reason why it happens.

- The explanatory principle: the tendency to explain ourselves unidirectionally and simplistically.

- The analytical method: we break down parts, analyze each one of them, and add them together with the hope of capturing and understanding the whole.

- Binary thinking: oscillates linearly between polarities (white and black, high and low, closed and open).

- Mathematical logic: we apply deductive logic to emotional problem solving.

- Objective reality: defending at all costs the search for and belief in a single reality, external to the gaze, and believing that it is possible to observe it objectively.

- The search for the single truth: understanding that there is only one truth and that it must be revealed in the hope of solving the problem.

- The insight : believing that discovering that external reality, that single truth, explaining and understanding it is the possibility of solving the problem.

- Cognitive inertia: tendency to apply repetitive thinking schemes and stereotype cognitive domino effect-type processes.

These components provide a way to approach problems, analyze them, and apply formulas to solve them.

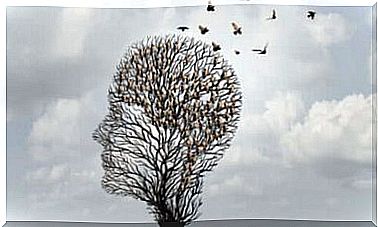

We all end up applying memorized solutions and reiterate more of the same, while continuing to apply repetitive schemas. This rigidity of mental schemas constitutes our cognitive model, of which we become prisoners if we fail to exercise our creativity and go beyond the limits of our mental boundaries.

The rational and logical left hemisphere is what predominates in analyzing the situation for a likely solution. Whereas the left, creative and more emotional, is relegated when it is the moment when it should be activated the most.

get out of the mental square

This process is clearly observed in intelligence problems, such as the nine-point problem . It is a simple problem and difficult to learn, but it is a clear example of failed attempts at a solution.

Nine dots are placed (as indicated in the next figure) and the instruction is to go through each of them without lifting the pencil and using only four straight lines.

When we analyze the image, after observing the instruction and looking at the nine points, it is impossible not to see the square. This is due to the Gestalt Proximity Perception Law: a succession of points form a straight line.

So, we get stuck in the grid, which causes the tests and solving attempts to get stuck on the perimeter of the square.

However, to be able to solve this problem, it is necessary to go beyond the illusion of this perimeter. Because, after all, he is exactly that: an illusion. The lines we are going to draw to solve the proposal must go beyond the limits of the imaginary square.

The square we see is not concrete, it is a metaphor for our own conceptual square, our rigid schemes that do not allow us to get out of our model of processing information.

To go beyond the perimeter of our model, creativity is needed. If we make an association with the theory of two hemispheres, the square is our left, rational, mathematical calculation. While the right (the lines that go beyond the perimeter) is more emotional and is what shows us the way to creativity.

Our brains systematize not only content, but also processes, more specifically ways of processing information. On the other hand, we are so imbued with rational logic that we apply formulas based on it and forget that human problems are mainly governed by emotions.

With this base and living up to the phrase “Man is an animal of habits” , we apply the same formula several times despite obtaining the opposite result to what we want to obtain. Meanwhile, we question the results and not the assumptions that lead us to them.

When researching the reason for the maintenance of failed solution attempts, in addition to the systematization of mental operations, it is observed that some solution attempts offer a momentary relief.

For example, a lady is distressed and naturally searching for the meaning of her sadness. So she sees the gray, rainy day and considers it the cause of her discomfort. Clearly, this does not transform your state, but this momentary justification gives you a certain reassurance.

Many systems try unsuccessfully

Failed attempts at a solution do not refer exclusively to personal initiatives. A person is involved in a series of failed personal attempts and, after spending years systematizing the same process, he has become more vulnerable and more dependent on the environment around him, and he turns to it in the search for answers that bring him closer to improvement.

This means that, among unsuccessful attempts, in principle, personal attempts are observed, which are those that the same person makes and repeats in favor of a solution. Among these attempts are what I call mantras . For example: “This won’t happen to me, it won’t happen to me!”, “I hope it works, hopefully!” .

There are also professional attempts in which different people with knowledge of the subject are sought for help with the solution.

And, finally, there are attempts by affectionately close people (neighbors, friends, families, etc.) to give useful advice that is sometimes useless. That is, advice that motivates and encourages us to move forward, but that gives us ineffective answers, or at least comforts us about what happened.

Many of them motivate us as pastors: “You can do it, you can do it!” . The point is that, in addition to not finding a solution, we are caught between the internal demand for everything to work out and the external “you can do it”. And this situation generates so much anxiety that it doesn’t benefit the resolution of the problem.

If we continue in this inertia, we will be able to resolve very little. Let’s see if this metaphor clarifies the issue: we’re halfway through a football game, we feel like we’re going to lose the match, we duck our heads and see the ball rolling in the distance. This is a negative formula. What should we do?

The recommendation is: keep the ball at your feet, dominate it, stop for a while and lift your head to know which direction to go. If you continue to act like this, you can pass it on to more experienced players, or kick towards the goal… Any option is valid, except to insist on ineffectiveness.